Seven things you need to know about climate change in Eastern and Southern Africa

Somalia has been hit by torrential seasonal rains and disastrous floods since October 2023, affecting more than 2.4 million people.

“The climate crisis is without doubt a humanitarian crisis […] it is hitting the most vulnerable people first, worst and longest – people, communities and countries already weakened by violence, insecurity, political instability, economic inequality and poverty.” Assistant Secretary-General and Deputy Emergency Relief Coordinator Joyce Msuya at the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28).

The climate crisis is causing a vicious circle of vulnerability that makes it harder for affected communities to recover, with women, children, older people and people with disabilities experiencing disproportionate impacts.

More To Read

- What’s at stake in the COP30 negotiations?

- Major global emitters off track, no country strong enough to meet climate targets - report

- African activists rally and challenge COP30 agenda

- Ethiopia hosting COP32 a ‘win for the Horn of Africa’, IGAD says

- AU congratulates Ethiopia on winning bid to host COP32 in Addis Ababa

- Power utilities raise clean energy investment plans by 26 per cent in major Net Zero push

As participants at COP28 this December discussed and implemented ways to accelerate action on mitigation, adaptation, loss and damage, and climate finance, we look at how climate change is affecting Eastern and Southern Africa.

1. A third of countries vulnerable to climate change are in Eastern and Southern Africa

Twenty-eight of the countries most vulnerable to climate change are in Eastern and Southern Africa, according to the ND-GAIN country index. But behind that statistic lies a human reality — people in Mozambique, South Sudan, Sudan, Zimbabwe and many more countries are facing increasingly frequent and intense storms, cyclones, floods and droughts that are causing extensive loss and damage.

The toll is visible in the rising number of people who need humanitarian assistance in sub-Saharan Africa, spiking from 110 million in 2021 to 168 million in 2023.

Most water sources in Kuku Ward, Kenya have dried up due to multiple years of failed rains. (Photo: OCHA/Maria Reaney)

Most water sources in Kuku Ward, Kenya have dried up due to multiple years of failed rains. (Photo: OCHA/Maria Reaney)

Samuel, a member of a community in Kajiado County, Kenya, says: “Close to 3,000 Maasai men have abandoned their families and moved to coastal towns such as Mombasa and Malindi to find work.

As a result, many women resorted to collecting spoiled tomatoes in irrigation farms and walking across the border to Tanzania at night to sell them, as they became the new heads of families and chief breadwinners, needing to provide food for their children.”

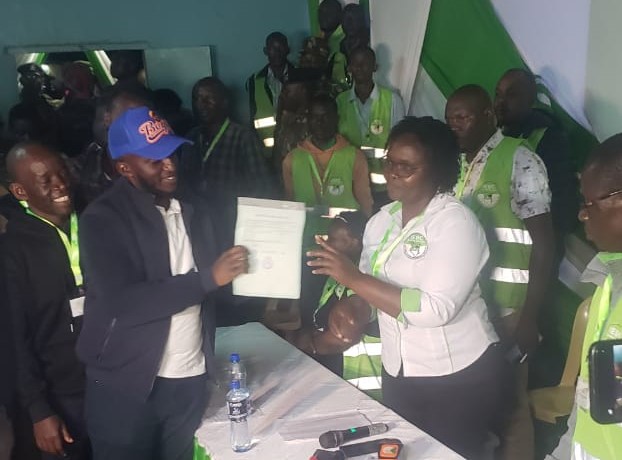

2. The region’s worst drought in recent history left 32 million people facing severe food insecurity

Five consecutive poor rainy seasons – the region’s longest drought in recent history – left more than 32 million people facing high levels of acute food insecurity in Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia in 2022.

The collective efforts of local communities, aid agencies, authorities and donors averted the worst outcomes, but research found that human-induced climate change was a major factor in this humanitarian emergency.

Women and children are 14 times more likely than men to die during natural disasters and crises. This is due to gender-specific barriers and inequalities that affect people’s exposure, vulnerability, preparedness and coping mechanisms. Samuel’s testimony above brings to light the drought’s double impact on women in Kenya.

Debo fled to a displacement site in Ethiopia. (Photo: IOM)

Debo fled to a displacement site in Ethiopia. (Photo: IOM)

3. Climate change is exacerbating food insecurity

Somalia has been hit by torrential seasonal rains and disastrous floods since October 2023, affecting more than 2.4 million people.

Rains were a relief after years of drought, but extreme climatic shocks threatened food production due to crop and livestock loss. Somalia is just one example of how the climate crisis, coupled with insecurity, has affected food systems, food production, food access and food utilization.

Cyclones, floods and swarms of desert locusts also increased humanitarian needs in Africa, with nearly one in four people (24 per cent of the population) facing severe food insecurity in 2022. Eastern and Southern Africa are among the worst-affected regions.

Children swim in the flood waters in Baidoa, Somalia. (Photo: OCHA/Ayub Ahmed)

Children swim in the flood waters in Baidoa, Somalia. (Photo: OCHA/Ayub Ahmed)

4. Weather-related events exacerbate displacement

Last year, disasters triggered 32.6 million internal displacements globally, 98 per cent of which were caused by weather-related factors, according to IOM.

By the end of 2022, Eastern and Southern Africa hosted approximately 26 million displaced people – both internally and across international borders – due to a mix of conflict- and climate-related shocks.

People such as Debo and her family often use migration as a coping mechanism and a way to mitigate the impact of climate change. However, this leaves affected communities in worse-off conditions without sustainable livelihoods, and it hampers their return home.

A Unicef study shows that Ethiopia and Somalia are among the countries most exposed to drought-related child displacement – of the 1.3 million children internally displaced across 15 countries between 2016 and 2021, more than half (730,000) were in Somalia and 340,000 in Ethiopia.

5. Rising temperatures are linked to deadlier natural disasters and diseases

The 2022 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change observed that as the global average of temperatures rises, Eastern and Southern Africa are expected to see an increase in average tropical cyclone wind speeds, associated rains and the proportion of destructive tropical cyclones.

For example, Madagascar is increasingly vulnerable to the climate crisis through rising temperatures, erratic rain patterns, and more frequent and severe extreme weather events. In October this year, the country was hit by temperatures that broke many high- and low-temperature records. This would not have occurred without human-induced climate change.

Earlier this year, Cyclone Freddy was a testimony to the impact of climatic shocks. It was the world’s strongest and longest-lasting tropical cyclone ever recorded, and it caused extensive damage in Madagascar, Malawi and Mozambique.

Extreme climatic events are also correlated to an increased incidence of foodborne and waterborne diseases, such as cholera, according to the World Meteorological Organisation.

6. Shifting weather patterns impact conflict

Predictions show that Eastern Africa is among the regions vulnerable to climate-related (violent) conflict due to competition over shrinking fertile land.

Before the conflict in Sudan erupted in April 2023, that country was already struggling with shifting weather patterns and environmental decline that had exacerbated tensions over scarce land and water resources.

Residents collect water from a rehabilitated reservoir on the outskirts of Um Naam Um village, Sudan. (Photo: UNEP/Lisa Murray)

Residents collect water from a rehabilitated reservoir on the outskirts of Um Naam Um village, Sudan. (Photo: UNEP/Lisa Murray)

UNEP noted that at least 40 per cent of all internal conflicts in Sudan over the last 60 years can be linked to competition over natural resources. For example, in the Blue Nile, natural resources played a role in defining conflict dynamics. Erratic rainfall, longer dry spells and more frequent floods are causing livestock, land availability and reliable water sources to fall short of demands.

7. Extreme weather patterns increase vulnerabilities

“In many cases, climate change is overtaking other factors as the predominant driver of humanitarian need.” Assistant Secretary-General and Deputy Emergency Relief Coordinator Joyce Msuya at the 28th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP28).

We cannot curb human suffering without addressing the climate crisis.

That’s why the humanitarian system is adapting and responding, helping people most affected by emergencies and building their resilience to climate shocks. At COP28, OCHA launched its UN Central Emergency Response Fund Climate Action Account. The Account will accelerate the humanitarian response to climate-related disasters and expand the use of anticipatory action to help communities prepare for and get ahead of predictable climate-related emergencies before they strike.

As the climate crisis deepens, additional finance dedicated to addressing climate-related disasters is urgently needed.

Top Stories Today